Loops and Conditional Logic

Last updated on 2024-07-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I do the same operations on many different values?

- How can my programs do different things based on data values?

Objectives

- identify and create loops

- use logical statements to allow for decision-based operations in code

This episode contains two lessons:

Repeating Actions with Loops

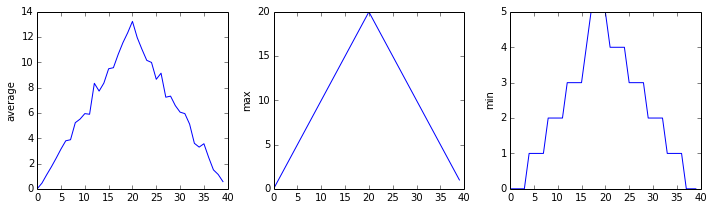

In the episode about visualizing

data, we will see Python code that plots values of interest from our

first inflammation dataset (inflammation-01.csv), which

revealed some suspicious features.

We have a dozen data sets right now and potentially more on the way if Dr. Maverick can keep up their surprisingly fast clinical trial rate. We want to create plots for all of our data sets with a single statement. To do that, we’ll have to teach the computer how to repeat things.

An example task that we might want to repeat is accessing numbers in a list, which we will do by printing each number on a line of its own.

In Python, a list is basically an ordered

collection of elements, and every element has a unique number associated

with it — its index. This means that we can access elements in a list

using their indices. For example, we can get the first number in the

list odds, by using odds[0]. One way to print

each number is to use four print statements:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is a bad approach for three reasons:

Not scalable. Imagine you need to print a list that has hundreds of elements. It might be easier to type them in manually.

Difficult to maintain. If we want to decorate each printed element with an asterisk or any other character, we would have to change four lines of code. While this might not be a problem for small lists, it would definitely be a problem for longer ones.

Fragile. If we use it with a list that has more elements than what we initially envisioned, it will only display part of the list’s elements. A shorter list, on the other hand, will cause an error because it will be trying to display elements of the list that do not exist.

ERROR

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

IndexError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-3-7974b6cdaf14> in <module>()

3 print(odds[1])

4 print(odds[2])

----> 5 print(odds[3])

IndexError: list index out of rangeHere’s a better approach: a for loop

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7This is shorter — certainly shorter than something that prints every number in a hundred-number list — and more robust as well:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11The improved version uses a for loop to repeat an operation — in this case, printing — once for each thing in a sequence. The general form of a loop is:

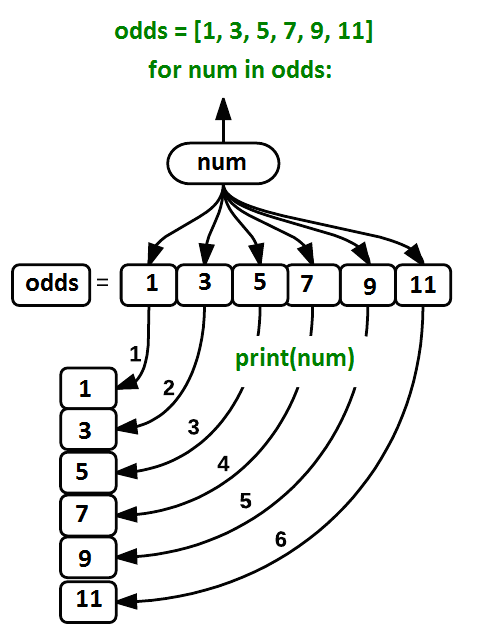

Using the odds example above, the loop might look like this:

where each number (num) in the variable

odds is looped through and printed one number after

another. The other numbers in the diagram denote which loop cycle the

number was printed in (1 being the first loop cycle, and 6 being the

final loop cycle).

We can call the loop

variable anything we like, but there must be a colon at the end of

the line starting the loop, and we must indent anything we want to run

inside the loop. Unlike many other languages, there is no command to

signify the end of the loop body (e.g., end for);

everything indented after the for statement belongs to the

loop.

What’s in a name?

In the example above, the loop variable was given the name

num as a mnemonic; it is short for ‘number’. We can choose

any name we want for variables. We might just as easily have chosen the

name banana for the loop variable, as long as we use the

same name when we invoke the variable inside the loop:

OUTPUT

1

3

5

7

9

11It is a good idea to choose variable names that are meaningful, otherwise it would be more difficult to understand what the loop is doing.

Here’s another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

PYTHON

length = 0

names = ['Curie', 'Darwin', 'Turing']

for value in names:

length = length + 1

print('There are', length, 'names in the list.')OUTPUT

There are 3 names in the list.It’s worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step.

Since there are three names in names, the statement on line

4 will be executed three times. The first time around,

length is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and

value is Curie. The statement adds 1 to the

old value of length, producing 1, and updates

length to refer to that new value. The next time around,

value is Darwin and length is 1,

so length is updated to be 2. After one more update,

length is 3; since there is nothing left in

names for Python to process, the loop finishes and the

print function on line 5 tells us our final answer.

Note that a loop variable is a variable that is being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over, and we can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables as well:

PYTHON

name = 'Rosalind'

for name in ['Curie', 'Darwin', 'Turing']:

print(name)

print('after the loop, name is', name)OUTPUT

Curie

Darwin

Turing

after the loop, name is TuringNote also that finding the length of an object is such a common

operation that Python actually has a built-in function to do it called

len:

OUTPUT

4len is much faster than any function we could write

ourselves, and much easier to read than a two-line loop; it will also

give us the length of many other data types we haven’t seen yet, so we

should always use it when we can.

From 1 to N

Python has a built-in function called range that

generates a sequence of numbers range can accept 1, 2, or 3

parameters.

- If one parameter is given,

rangegenerates a sequence of that length, starting at zero and incrementing by 1. For example,range(3)produces the numbers0, 1, 2. - If two parameters are given,

rangestarts at the first and ends just before the second, incrementing by one. For example,range(2, 5)produces2, 3, 4. - If

rangeis given 3 parameters, it starts at the first one, ends just before the second one, and increments by the third one. For example,range(3, 10, 2)produces3, 5, 7, 9.

Using range, write a loop that uses range

to print the first 3 natural numbers:

OUTPUT

1

2

3The body of the loop is executed 6 times.

Summing a List

Write a loop that calculates the sum of elements in a list by adding

each element and printing the final value, so

[124, 402, 36] prints 562

Computing the Value of a Polynomial

The built-in function enumerate takes a sequence (e.g.,

a list) and generates a new sequence of the

same length. Each element of the new sequence is a pair composed of the

index (0, 1, 2,…) and the value from the original sequence:

The code above loops through a_list, assigning the index

to idx and the value to val.

Suppose you have encoded a polynomial as a list of coefficients in the following way: the first element is the constant term, the second element is the coefficient of the linear term, the third is the coefficient of the quadratic term, etc.

OUTPUT

97Write a loop using enumerate(coefs) which computes the

value y of any polynomial, given x and

coefs.

Making Choices with Conditional Logic

How can we use Python to automatically recognize different situations we encounter with our data and take a different action for each? In this lesson, we’ll learn how to write code that runs only when certain conditions are true.

Conditionals

We can ask Python to take different actions, depending on a

condition, with an if statement:

OUTPUT

not greater

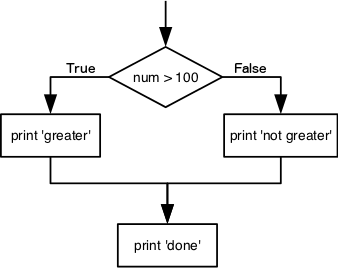

doneThe second line of this code uses the keyword if to tell

Python that we want to make a choice. If the test that follows the

if statement is true, the body of the if

(i.e., the set of lines indented underneath it) is executed, and

“greater” is printed. If the test is false, the body of the

else is executed instead, and “not greater” is printed.

Only one or the other is ever executed before continuing on with program

execution to print “done”:

Conditional

statements don’t have to include an else. If there

isn’t one, Python simply does nothing if the test is false:

PYTHON

num = 53

print('before conditional...')

if num > 100:

print(num, 'is greater than 100')

print('...after conditional')OUTPUT

before conditional...

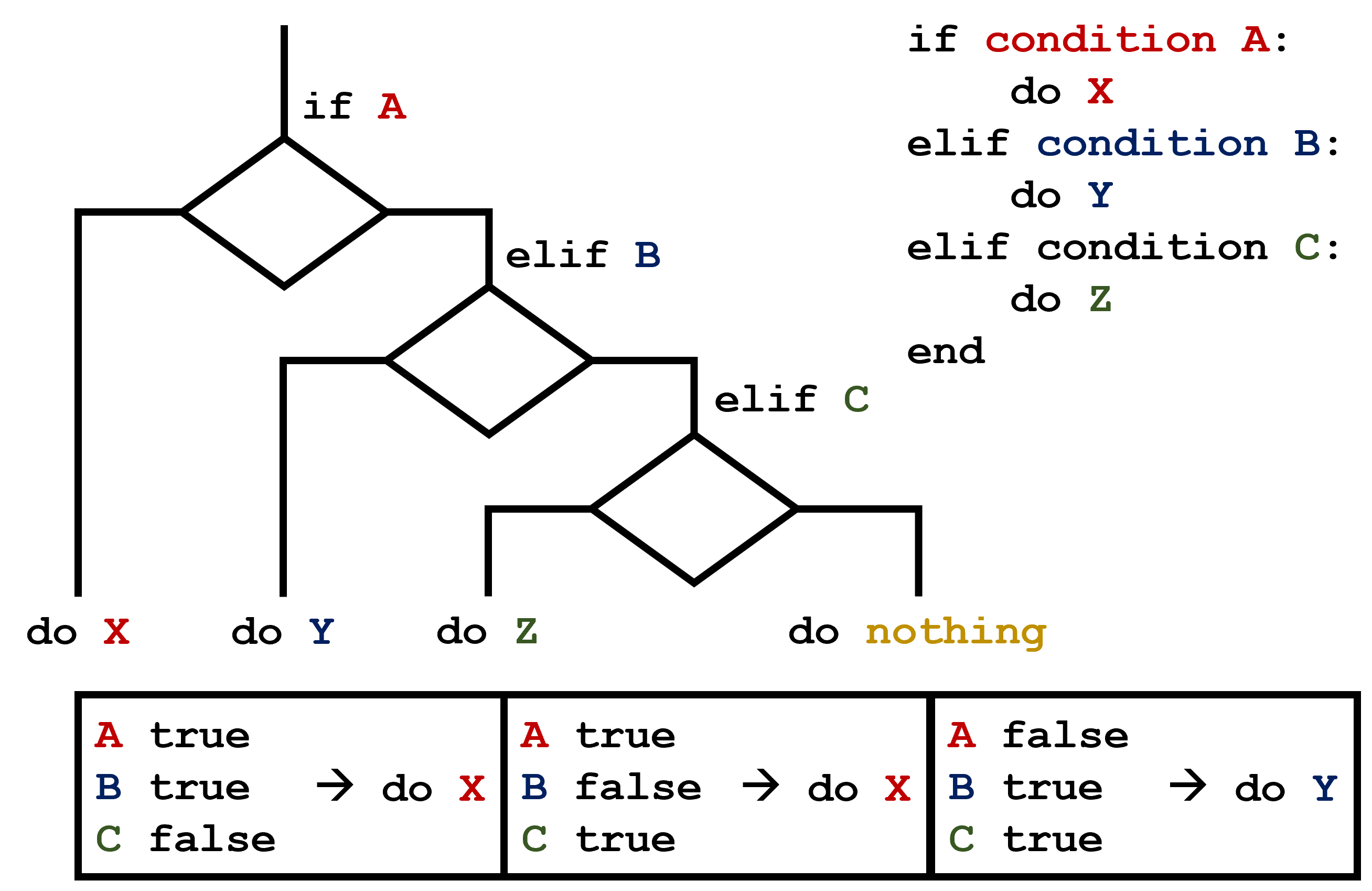

...after conditionalWe can also chain several tests together using elif,

which is short for “else if”. The following Python code uses

elif to print the sign of a number.

PYTHON

num = -3

if num > 0:

print(num, 'is positive')

elif num == 0:

print(num, 'is zero')

else:

print(num, 'is negative')OUTPUT

-3 is negativeNote that to test for equality we use a double equals sign

== rather than a single equals sign = which is

used to assign values.

Comparing in Python

Along with the > and == operators we

have already used for comparing values in our conditionals, there are a

few more options to know about:

-

>: greater than -

<: less than -

==: equal to -

!=: does not equal -

>=: greater than or equal to -

<=: less than or equal to

We can also combine tests using and and or.

and is only true if both parts are true:

PYTHON

if (1 > 0) and (-1 >= 0):

print('both parts are true')

else:

print('at least one part is false')OUTPUT

at least one part is falsewhile or is true if at least one part is true:

OUTPUT

at least one test is true

True and False

True and False are special words in Python

called booleans, which represent truth values. A statement

such as 1 < 0 returns the value False,

while -1 < 0 returns the value True.

Checking Our Data

Now that we’ve seen how conditionals work, we can use them to check

for the suspicious features we saw in our inflammation data. We are

about to use functions provided by the numpy module again.

Therefore, if you’re working in a new Python session, make sure to load

the module with:

From the first couple of plots, we saw that maximum daily inflammation exhibits a strange behavior and raises one unit a day. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to detect such behavior and report it as suspicious? Let’s do that! However, instead of checking every single day of the study, let’s merely check if maximum inflammation in the beginning (day 0) and in the middle (day 20) of the study are equal to the corresponding day numbers.

PYTHON

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')We also saw a different problem in the third dataset; the minima per

day were all zero (looks like a healthy person snuck into our study). We

can also check for this with an elif condition:

And if neither of these conditions are true, we can use

else to give the all-clear:

Let’s test that out:

PYTHON

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-01.csv', delimiter=',')

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')

elif numpy.sum(numpy.amin(data, axis=0)) == 0:

print('Minima add up to zero!')

else:

print('Seems OK!')OUTPUT

Suspicious looking maxima!PYTHON

data = numpy.loadtxt(fname='inflammation-03.csv', delimiter=',')

max_inflammation_0 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[0]

max_inflammation_20 = numpy.amax(data, axis=0)[20]

if max_inflammation_0 == 0 and max_inflammation_20 == 20:

print('Suspicious looking maxima!')

elif numpy.sum(numpy.amin(data, axis=0)) == 0:

print('Minima add up to zero!')

else:

print('Seems OK!')OUTPUT

Minima add up to zero!In this way, we have asked Python to do something different depending

on the condition of our data. Here we printed messages in all cases, but

we could also imagine not using the else catch-all so that

messages are only printed when something is wrong, freeing us from

having to manually examine every plot for features we’ve seen

before.

C gets printed because the first two conditions,

4 > 5 and 4 == 5, are not true, but

4 < 5 is true. In this case, only one of these

conditions can be true for at a time, but in other scenarios multiple

elif conditions could be met. In these scenarios, only the

action associated with the first true elif condition will

occur, starting from the top of the conditional section.

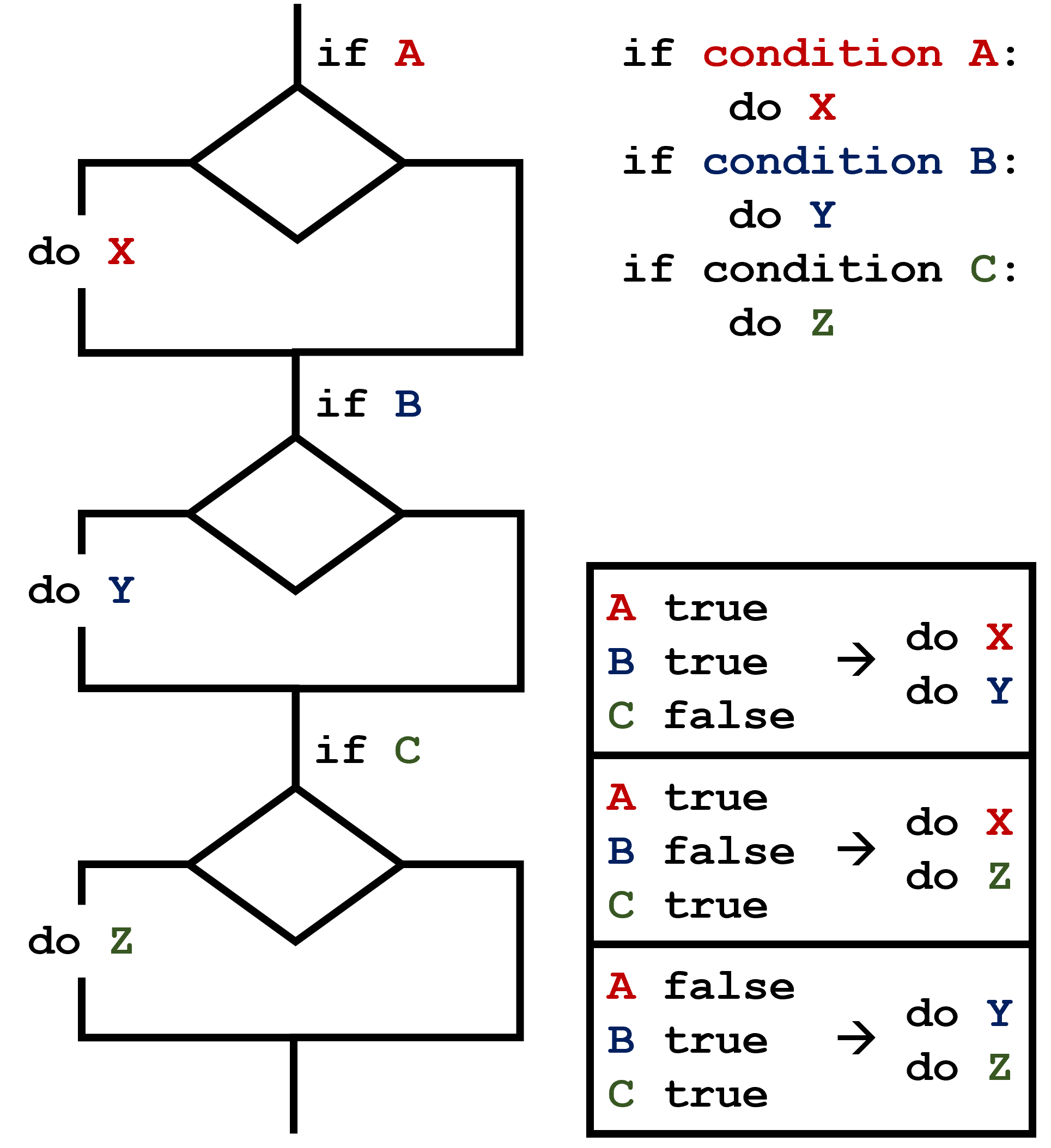

This contrasts with the case of multiple if statements,

where every action can occur as long as their condition is met.

What Is Truth?

True and False booleans are not the only

values in Python that are true and false. In fact, any value

can be used in an if or elif. After reading

and running the code below, explain what the rule is for which values

are considered true and which are > considered false.

That’s Not Not What I Meant

Sometimes it is useful to check whether some condition is

not true. The Boolean operator not can do this

explicitly. After reading and running the code below, write some

if statements that use not to test the rule

that you formulated in the previous challenge.

Close Enough

Write some conditions that print True if the variable

a is within 10% of the variable b and

False otherwise. Compare your implementation with your

partner’s. Do you get the same answer for all possible pairs of

numbers?

There is a built-in

function abs that returns the absolute value of a

number:

OUTPUT

12In-Place Operators

Python (and most other languages in the C family) provides in-place operators that work like this:

PYTHON

x = 1 # original value

x += 1 # add one to x, assigning result back to x

x *= 3 # multiply x by 3

print(x)OUTPUT

6Write some code that sums the positive and negative numbers in a list separately, using in-place operators. Do you think the result is more or less readable than writing the same without in-place operators?

PYTHON

positive_sum = 0

negative_sum = 0

test_list = [3, 4, 6, 1, -1, -5, 0, 7, -8]

for num in test_list:

if num > 0:

positive_sum += num

elif num == 0:

pass

else:

negative_sum += num

print(positive_sum, negative_sum)Here pass means “don’t do anything”. In this particular

case, it’s not actually needed, since if num == 0 neither

sum needs to change, but it illustrates the use of elif and

pass.

Sorting a List Into Buckets

In our data folder, large data sets are stored in files

whose names start with “inflammation-” and small data sets – in files

whose names start with “small-”. We also have some other files that we

do not care about at this point. We’d like to break all these files into

three lists called large_files, small_files,

and other_files, respectively.

Add code to the template below to do this. Note that the string

method startswith

returns True if and only if the string it is called on

starts with the string passed as an argument, that is:

OUTPUT

TrueBut

OUTPUT

FalseUse the following Python code as your starting point:

PYTHON

filenames = ['inflammation-01.csv',

'myscript.py',

'inflammation-02.csv',

'small-01.csv',

'small-02.csv']

large_files = []

small_files = []

other_files = []Your solution should:

- loop over the names of the files

- figure out which group each filename belongs in

- append the filename to that list

In the end the three lists should be:

PYTHON

for filename in filenames:

if filename.startswith('inflammation-'):

large_files.append(filename)

elif filename.startswith('small-'):

small_files.append(filename)

else:

other_files.append(filename)

print('large_files:', large_files)

print('small_files:', small_files)

print('other_files:', other_files)- Write a loop that counts the number of vowels in a character string.

- Test it on a few individual words and full sentences.

- Once you are done, compare your solution to your neighbor’s. Did you make the same decisions about how to handle the letter ‘y’ (which some people think is a vowel, and some do not)?

- Use

for variable in sequenceto process the elements of a sequence one at a time. - The body of a

forloop must be indented. - Use

len(thing)to determine the length of something that contains other values. - Use

if conditionto start a conditional statement,elif conditionto provide additional tests, andelseto provide a default. - The bodies of the branches of conditional statements must be indented.

- Use

==to test for equality. -

X and Yis only true if bothXandYare true. -

X or Yis true if eitherXorY, or both, are true. - Zero, the empty string, and the empty list are considered false; all other numbers, strings, and lists are considered true.

-

TrueandFalserepresent truth values.